In my last blog, I delved into the magic of storytelling–or more specifically, the birth of stories, a subject that came up in my interview with Liz Adair. I promised to share the memoir that came to me in an afternoon, the first story I wrote. The drawings, which i’m embarrased to claim, are a child’s memory.

Here it is

““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““`

Stagg Field, 1943

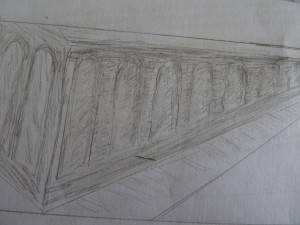

Every day as I grew up, the Stagg Field wall stretched its length between me and school, between me and home, between me and anywhere. Across the street from the old stadium was the campus backside, a line of gothic stone enfolding and protecting. From the front it was the

University of Chicago, set back a pace from the city by the broad green ribbon of the Midway, insulated by parks at either end. One that side, Rockefeller Chapel rose like a crown jewel; our parents took us up into the bell tower, sometimes, on Sunday, but we lived around back, near the field.

In the summer that wall blinding; no tree or shrub broke the glare of stone, concrete, and more stone, and as you looked down its length you could see the heat waves dancing before you pitched through the prickly, airless space. In the winter it was a wind tunnel, roofed by the dirty Chicago sky. It was an empty place, a scar where the University cut herself off from her athletic past.

And it was always there. Like a swimmer going under, I’d duck my head for the four times daily trip. Sometimes I was a sea captain, fighting the gales around Cape Horn, or a gallant child-hero dragging my brother safely through arctic wastes; sometimes I was an Arab driving a caravan toward an oasis. But more often I watched my feet, absorbed their rhythm as they matched their monotony to the monotony of the stone beside me, to the steady procession of cracks beneath me, and gave myself into a trance.

When I surfaced at Ellis Avenue, the homeward end, the gray towers ended too. Beyond Ellis was the university backyard, a litter of mismatched outbuildings where, among experiments and service plants, the faculty raised its young. Catty corner from the field was a squat yellow brick box with a Parthenon-like entry stuck to the front, facing campus. They kept sheep behind it. Down the street, if it was summer and the windows were open, you could hold your ears and watch black printing presses screech and clang, and listen to the men shouting to each other over the din. Behind that, surrounded by small buildings that gave off strange smells, the five-story chimney of the heating plant rose to mark the block. Beyond that was our alley.

On the front, the row of six-flats facing Drexel looked like any other row of Chicago six-flats, but in back, the three-story spider web of banisters, porches, and stairways overlooked chicken coops—university chicken coops. We woke to roosters every day, and if you walked with your ear to the board fence, a world of barnyard smells and noises rippled by. Except for that, it was a Chicago alley; we had Dominic, the vegetable man, who gave rides, and a milkman with a horse-drawn wagon, who didn’t—so you had to sneak. An ice cream truck, a monkey-grinder man, an accordion player, a knife sharpener, a brush peddler, a rag man–almost anyone might come through and there was an alley sonar for new arrivals. It signaled when the nose of a dump truck appeared at the end of the alley, inching its way between board fence and telephone poles, leaving mountains of coal to climb.

Between visits, we walked fences, played hide and seek in the web of porches, held secret meetings behind furnaces in dark basements, and tangled in wash lines. If you dropped a ball from a third floor porch, and you aimed right and didn’t hit a crack, it would bounce far enough for a friend leaning out from a second floor porch to catch, if her mother didn’t see her.

Then the fathers came home for dinner and everyone went in. The din that traveled up and down the airshafts faded, and it felt like the place under the carillon where there is a seal that no one steps on. “Crescat Scientia Vita Excolatur;” “Let Knowledge Grow, Life Will be Enriched.” My father sat and thought, and no one interrupted, even for the salt. Then all of a sudden he’d look up. “Al Smith was right,” he’d say. “Do you know who Al Smith was?” And he’d tell the story in a way that made Al’s rightness burn through. Another time it would be, “The Union generals were bums.” And he’d tell about Grant’s drinking or McClellan’s cowardice, even though McClellan was supposed to be a relative of ours. Other days he’d say nothing from the beginning of the meal to the end, and his face and eyes would shift and strain with inward rage—at ritual used to raise emotions and bind people to narrow visions—at failure to acknowledge freedom of the intellect to rise above passion, to search for truth. We watched and knew, for he was likely to turn to us, pare us to our rational bones to discover whether we were becoming what we were to be. He’d ask for answers then, for evidence, and I never had any. My alley self shrunk up or slipped away and left me stranded, unknowing everything I knew. There was no barnyard behind the alley fence; there was research.

And as I made my daily journey down Stagg Field’s length, I became more and more aware of those gothic towers rising across the street.

Once I’d made a dash for Hull Gate, the entrance to the quadrangles, aiming for the pond inside as though I owned the place. The dark water under the lily pads hid goldfish and turtles, which you could see if you sat very still on the stone bridge. I knew every alcove where you echoed, exactly how much the bottoms of your feet hurt when you jumped from each wide stone balustrade, which ones you could run down and which you couldn’t. I knew in which square you could find shouting sun and where the shade was very old and shivery. There was a tiny lovely chapel to peek into, but it was always very sad. I knew the hot places in the sidewalk where you could warm your undersides even as the cold bit your fingers. The important question then was deciding whether Mitchel Fountain was better spouting water in summer or covered for winter when you could run up its wooden roof, the echoes of your feet making all the surrounding spires take note.

But even then the sound faded and left the quiet bigger than before; the quadrangles again became scenic easements for the towers of the mind. Botany Pond was there for science.

So even then I ran back through the gate, away from those encircling expectancies, to the comfortable monotony of the unwanted field. There was a door in the wall, a gigantic, double-leaved iron-hasped castle door that give birth in its midriff, like a laugh, to a little door. On rare days the shell would condescend a peek—the little door would be open. It was the peephole in a giant shadow box, granting a glimpse of a magic world. All I remember were joggers running the track, football teams from other places practicing, but I’d watch spellbound until the empty bleachers shrunk the activity to silliness. Bleachers are usually empty, but these had the dusty sadness of a face no one wants anymore, and I think the field was grateful for that human flurry even as it reduced it to insignificance.

So even then I ran back through the gate, away from those encircling expectancies, to the comfortable monotony of the unwanted field. There was a door in the wall, a gigantic, double-leaved iron-hasped castle door that give birth in its midriff, like a laugh, to a little door. On rare days the shell would condescend a peek—the little door would be open. It was the peephole in a giant shadow box, granting a glimpse of a magic world. All I remember were joggers running the track, football teams from other places practicing, but I’d watch spellbound until the empty bleachers shrunk the activity to silliness. Bleachers are usually empty, but these had the dusty sadness of a face no one wants anymore, and I think the field was grateful for that human flurry even as it reduced it to insignificance.

Bits of memory jumped about in my mind, of our alley packed with cars, the din of horns and noisemakers, raccoon coats and pennants, and sitting in a third floor window watching the scoreboard through someone’s binoculars. I’m told I can have no such memory, that the University of Chicago stopped playing football before I was born—but it’s a fitting memory. What could I substitute? The name of Amos Alonzo Stagg? We used to roll it off our tongues, but I saw him once, and he was an old man—little and very wrinkled. A few stale football songs rattling around coffee houses? Some maroon and white football uniforms stolen for Halloween parties? The human sized door was usually closed and my four-times-daily walk a trudge—so I kept the memory.

One morning Pearl Harbor was bombed. We woke to find the adult world steamrolled, trying to shake out, to reorient. The smudgy chalk lines of everyday were wiped away and replaced by pen and ink. The railroads brought long unseen cousins and uncles to our house, all in uniform, pressed, with gold braid and shiny buttons, on their way to war. The living room where my father read was filled with students, gloriously transformed into officers, and then they were gone too. Life acquired new habits—ration stamps, paper drives and tinfoil balls. And songs. Hitler’s voice came over the short-wave, along with German voices singing as they marched—and we learned songs to match theirs. And every Saturday afternoon at the Frolic theater, newsreels showed jackboots marching through the silent streets of Europe.

Then a map went up on the dining room wall so the war could teach us our geography, and the Chicago Tribune produced endless words. And we learned to focus beyond, to comment, to evaluate, to judge. Little, after all, was different.

Except Stagg Field. Stagg Field acquired a mysterious life. How did we know? A child always knows when an adult is hiding something behind his back. Her walls were suddenly too stiff, her doors too closed; there was too much of the wrong kind of quiet—she was no longer empty; she was shut. Every passing school child knew something was going on in Stagg Field, and knew with equal certainty that it was “secret war work.” Every fedora pulled too low became a German, every overcoat too long a Jap, and the comings and goings at the West end of the field inspired new plots daily. The stories were ours, for our entertainment, to liven up the trudge along the wall.

But then one day the castle doors themselves began to open. Slowly. With great complaint. And when they were all the way open, they revealed two Sunshine Laundry trucks. Beside each truck stood a guard with a tommygun. Someone had stolen our spy thriller and turned it into a Marx Brothers comedy. In the days that followed, our nostrils and skins picked up the tension. We stopped telling spy stories.

One day when peeked through the fence to see the sheep behind the yellow brick corner building, I saw an armed guard instead of sheep. When my brother and I came back an hour later, on our way back to school, we stopped before we got to the corner because we couldn’t hear the street. It was missing. Instead we heard marching feet—jackboots come to Ellis Avenue. We crept forward and watched the squad of men that marched back and forth in the street that had taken cover. We ran. By the time we returned from school it was over—it happened and unhappened.

No one would—or could—explain. It was a time of odd silences, of breaks and pauses in adult sentences. So it remained suspended in memory for two years, until I stood looking down at the evening paper and understood.

Mushroom cloud

“Fifty thousand dead” “the scientists at the University of Chicago have succeeded” “the war is over” “splitting of the atom” “ten thousand dead” “heralds a new age” “Hiroshima” “under the decaying stands of an abandonned football fiels” “death toll” “breakthrough”

Words were blown free, subjects could not find predicates my mind could embrace. If the scientists had fathered fission who had fathered death? For a few days the university herself seemed shaken, turned and looked behind her aghast. At the dinner table, my father said nothing. His face was not abstracted; it was gray.

But it was atomic fission, not the bomb, that was born under the stands that day, and the soldiers were a suicide squad, not the war come home. The towers pulled themselves together and turned around again. “Science must be free and pure, and is in no way liable for the uses men find for its discoveries.” I don’t remember my father saying that; I remember the words as coming from the air we breathed, from the towers themselves, the sound of a congregation chanting its creed.

Sometimes my father stared at the table, but we were of the faith. When it came my turn, I walked the aisle of Rockefeller Chapel and received my confirmation. It’s nice to be ennobled. The dirty belching mill town where I grew up has felt its touch. Picasso’s beast spreads its

wings where I remember pawnshops; Alex Calder’s ‘Flamingo’ has lighted in a place I was not allowed to go; seasons are marked by Chagal’s mosaic instead of by the tone of the lake wind. Not long ago the workers of the mills and slaughterhouses, Sandburg’s “hog butchers of the world,” were transformed into Miro’s peasant, pitchfork pointed to the sky. I like to think I’m a part of that, but I know better. I received my monument twenty years after that December noon, when the university ordered the West Stands torn down and commissioned a monument to symbolize science’s gift to the world that day. Henry Moore gave us a mushroom cloud—set in stone. I can still feel the faculty’s shock, my father’s rage at that choice of symbol. They tore down the rest of the field and built a library that towers above that little ball of stone, but it doesn’t change anything. It is still mine, and I’m still standing there where the old field opened her shabby arms and received that bastard child.

Comments are closed.