I’ve talked before about how shifts in the language have changed the political climate. How, when “opponent” became “enemy,” “debate” became “battle,” and “compromise” was called “selling out” politics went to war. Our minds followed the words, and the climate soured; war words became an accurate description of political life—except to those of us who remember something different. Words express the reality, but when it comes to human activity, they also have the power to change it. For example, expressions like “those are just words” has led generations of Americans to treat words—except for swear words—as candidates for the dustbin. But I’m a writer; my mind sticks on words, and I’d like to talk about a few others that I think shape our political reality in destructive ways.

We are in an election year, so we will be hearing once again about “promises”—and how they were or were not kept. “Promises” are what parents make; the word belongs to the world where the promiser has the power to produce the results, and consciously or not, our minds shift into that domain. Conservatives complain that liberals treat government as a “Big Daddy,” and I think politicians who “promise” removal of all human suffering do promote such an attitude. “Promise” is, of course, short for “promise to work for,” but our minds don’t hear it that way. Listen, as these months go on, to the complaints that Biden didn’t keep his promises—as though the fault lies in the failure of one man.

“Promising” has been the political lingo for as long as I can remember, but I’ve watched other words gradually change their meaning as individualism increases its hold. Human rights of equality, justice, and freedom, ideals which I always understood to be goals, have become entitlements—conditions an oppressive government has denied or neglected. Gone is the essential fact that laws, good, bad, and indifferent, originated with the citizenry. The word “rights” is no longer paired with “responsibility,” as it was in my early life, and ideals the nation has not yet achieved have become the failures of corrupt, oppressive government. The pandemic has given us an ample dose of a world where concern for “the other fellow’s nose” has vanished.

entitlements—conditions an oppressive government has denied or neglected. Gone is the essential fact that laws, good, bad, and indifferent, originated with the citizenry. The word “rights” is no longer paired with “responsibility,” as it was in my early life, and ideals the nation has not yet achieved have become the failures of corrupt, oppressive government. The pandemic has given us an ample dose of a world where concern for “the other fellow’s nose” has vanished.

For me, this shift began legitimately with the Sixties’ demands for racial justice and protests against the Vietnam War. Demands that the government listen to the citizens is certainly appropriate and admirable, and confrontation demands government pay attention that was long overdue. Those movements led to the elimination of laws that legitimized racism—a giant step forward. But the continual use of confrontation on all fronts since then has paired the word “rights” with “oppression” rather than “responsibility” and generated a top-down view that it is government that is the cause rather than the result of all prejudice—and can fix it. Indeed, a student in one of my post-Sixties college classes told me, “Our parents said they fixed it all.”

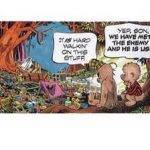

Paired with the view of government as provider, this top-down view of government as all powerful fixer and oppressor should worry us. Granted the movements of the Sixties were driven by adolescents, who do believe they can fix it all, and granted eliminating bad laws is a critical part of cultural change, it is not a healthy view of democracy. Our government is a mirror, reflecting what we are and will change when we change. Someone needs to remind our citizenry that we sent King George home. We told him we could do it ourselves.

Comments are closed.